Quittor

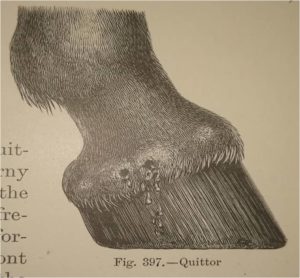

Quittor is an infection of the collateral cartilages. Left: An old blow-out site of a quittor. The infection may discharge several times in the same site; Right: This picture illustrates the depth of the lateral cartilage and why it is problematic if it becomes infected.

Older books defined quittor as simply an infection in the horse’s foot that could take on several different forms: cutaneous quittor (skin and underlying tissue), tendinous quittor (infection extending to tendons and ligaments), cartilaginous quittor (deeper infection in the lateral ungular cartilages), and sub-horny quittor (within the hoof). (Axe, J.W. The Horse: Its Treatment in Health and Disease. 1906)

Infections in the hoof can occur in several different sites (i.e. abscess, corn, thrush, etc.) so it helpful to assign a name specific to location. Today, quittor most commonly references the infection of the lateral cartilages. The term quittor is thought to be first used around 1703 and likely comes from the Middle English and Old French, “quiture” meaning pus or discharge. Other origins might include the Low German, “kwader” meaning rottenness (mirriam-webstar.com/dictionary/quittor).

Quittor can be caused by a puncture, trauma, or treading from heel calks on working horses. For this reason, quittor is fairly rare now. Horses are used less so the disease is observed less. Still a case does come up every so often. One of my dad’s favorite horses ended up with a quittor when, while jumping a tree in pursuit of a cow, a pine branch jabbed the horse in the coronet on the lateral side of the right front foot. As the wound healed, the infection went deep into the ungular cartilage. Even though the wound seemed to heal up outwardly, the internal infection sprang up again later and blew out at the site of the old wound. In this case, the horse was chronically lame from the condition and never made a full recovery.

Not every horse becomes lame from a quittor. In other cases, the horse may be intermittently lame as the infection blows out again and again. It might be comparable to a person who gets chronic paronychia (a painful swelling around the fingernails due to a bacterial infection, usually introduced by an injury). Recently, I had this in my middle finger around my fingernail. The swelling was incredibly painful if it was bumped or touched. The only relief came when, after soaking it with Epsom salts for a few days, the infection discharged next to my fingernail. Now there is a slight mark where it came out.

Quittor is an abscess with some distinctions. An abscess usually discharges its contents once, while the bacterial infection in quittor is never truly cleared up; causing multiple discharges even after apparent healing. (Reeks. H.C. Diseases of the Horse’s Foot. 1925).

Because the deep bacterial infection causes continual “blow-outs”, the principle of treatment for quittor is to remove the infection. This is not easily done because of the deep location of the lateral cartilage and the extensive venous circulation adjacent to the cartilage. Veterinarians most likely will recommend curetting (scraping) the infection or surgical removal of the necrotic portion of cartilage if possible. Necrotic cartilage can be recognized by its dark blue or reddish blue appearance. Only in some extreme cases, is the entire cartilage removed. It is also recommended that the horse should be medically managed by the veterinarian with systemic antibiotics, foot soaks, and sometimes injection of antiseptics into the wound (Adams, O.R., Baxter, G.M. Adam and Stashak’s Lameness in Horses. 6th ed. 2011).

As stated before, quittor is rare. Horses today that get a quittor should be treated by a veterinarian as soon as possible. As with most diseases of the foot, the horse’s prognosis is better if treated sooner. Horse’s that become chronically lame due to a deep infection have a much poorer chance at fully recovering from the condition (Butler, K.D and J.R. Principles of Horseshoeing. 3rd ed. 2004).

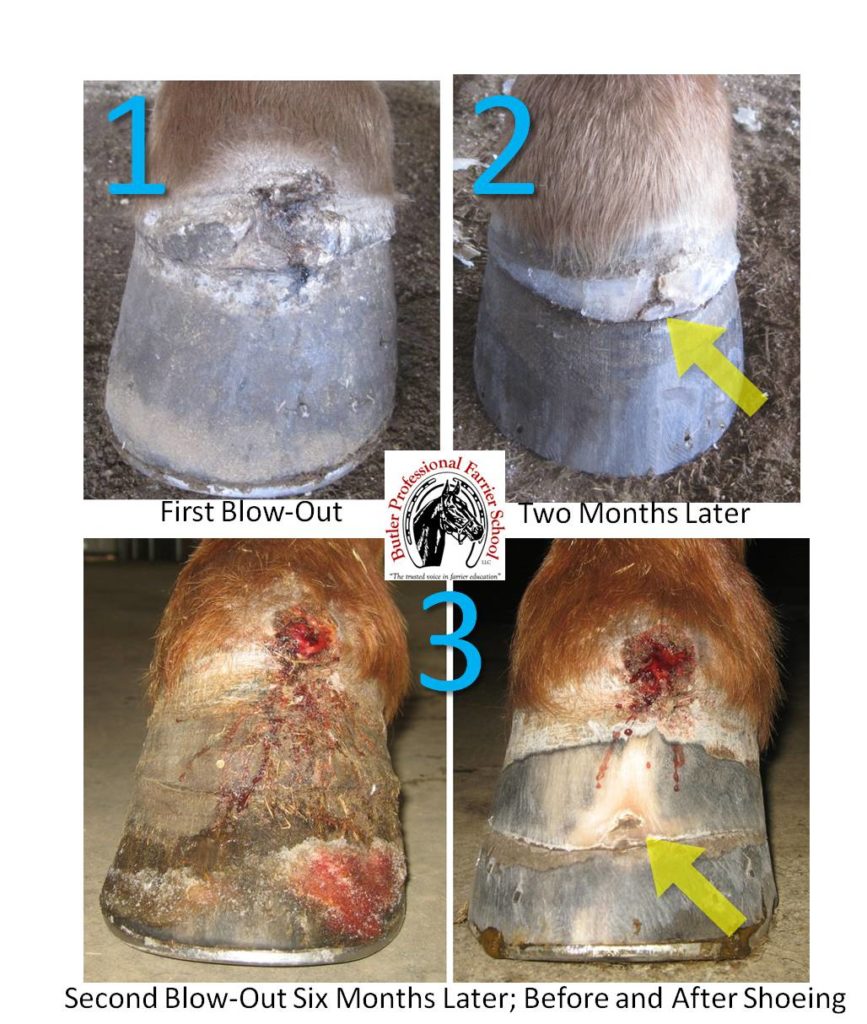

Though this series of pictures does not illustrate a quittor, it does show a similar sequence of events. 1) This horse had an abscess that broke at the dorsal coronary band. 2) Two months later, when the horse was brought back to be trimmed, evidence of the old abscess (yellow arrow) was still there though it had grown down a little more than a half inch. 3) Six months later in the wintertime, the horse was brought back with a newly broken abscess in the same place. After the horse was trimmed and shod, evidence of the first break was more visible (yellow arrow). This suggests that, while not a quittor because of location, the infection had not cleared up completely from the first discharge of the abscess. In this case, the bacterial infection seemed to have discharged completely the second time because the horse had no known subsequent blow-outs.

Related Posts

-

©2013 Doug Butler PhD, CJF, FWCF Butler Professional Farri...Apr 10, 2013 / 0 comments

-

Driving horseshoe nails accurately, consistently and safely ...May 24, 2019 / 0 comments

-

Answer: A hoof that is proportional to the horse’s bod...Dec 07, 2009 / 0 comments

Comments1

Leave a Comment! Cancel reply

Blog Categories

- Anatomy

- Best Business Practices

- Conformation

- Current Events

- Customer Service

- Draft Horse Shoeing

- Equine Soundness

- Essential Anatomy Kit

- Farrier Careers

- Farrier training

- Foal soundness

- Horse Care

- Horse Foot Care

- Horse Owner Tips

- Horsemanship

- Horseshoeing

- Horseshoeing History

- Iron and Forge Work

- Student Spotlight

- Uncategorized

- Veterinary Care

Blog Archives

Contact Us

Butler Professional Horseshoeing School

495 Table Road

Crawford, NE 69339

(800) 728-3826

jacob@dougbutler.com

Subscribe to Our Blog

Get Our Free e-Book!

If you think you want to become a farrier (or know someone who does), this book can help you make that decision. Horse owners will learn the importance of choosing a qualified farrier and how to select the “right” one.

[ Get the e-Book Now! ]

- Follow:

Quittor is a subject that should not be relegated to historical textbooks–thanks for keeping it in the consciousness of your readers! I do think that people stumble over the word, or how to spell and pronounce it, so maybe it’s time to start a campaign to give it a new name?