Mechanics of the Navicular Bone

The navicular bone is a small bone with a big function. Navicular comes from the latin word “navis” meaning boat because of the bone’s boat-like shape. It is attached in the foot via the impar ligament (blue) to the coffin bone (P3) and the collateral ligaments of the navicular bone (black) to the distal end of the long pastern bone (P1).

The navicular bone in the foot of the horse is known more for the problems it can create (i.e. navicular syndrome) rather than for its actual function. Navicular syndrome or navicular disease often results in heel pain due to a problem associated with the navicular region; not just the bone. The condition is usually treated by the farrier with the application of bar shoes and wedge pads too alleviate pressure to the navicular area. Some conditions are made better by veterinarian-prescribed drugs.

Why does the horse have a navicular bone? What purpose does it serve? Navicular gets its word origin from the Latin, “navis” meaning boat (think “Navy”). The bone gets its name because it is shaped like a boat. The navicular bone in the horse is not in the same place as the human. In the human, the navicular bone is positioned in the ankle and its placement is comparable to the central tarsal bone in the horse’s hock. The scaphoid bone in the human’s wrist used to be known as the navicular bone and its placement is comparable to the radial carpal bone in the horse’s knee. Older books refer to the bone in the human wrist as a navicular bone. To distinguish it from the navicular bone in the ankle, it is now commonly known as the scaphoid—which, interestingly, also means “boat” but in Greek instead of Latin.

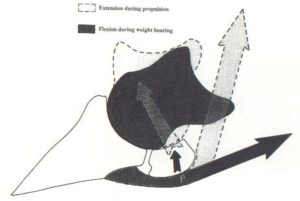

The navicular bone acts as a fulcrum to keep the direction of the pull on the deep flexor tendon constant. Reference: Denoix J-M: Vet Clinics of N. A., Aug 1994, pg 308.

The navicular bone in the horse is positioned between the third phanlanx (P3 or coffin bone) and the second phalanx (P2 or short pastern bone) at the coffin joint. There is no human counterpart as this joint in humans is the last joint in the finger, just behind the fingernail. The navicular bone is necessary at this joint because of the range of motion and potential concussion that occurs at this site. In his Manual of Veterinary Physiology, Major- General Sir Frederick Smith states, “The [coffin] joint is the centre of the entire movement of the leg; the body rotates over it.” (1921) The incredible amount of force and articulation placed on the joint makes it necessary to have something to counteract shock. The navicular bone provides this counteraction by yielding under pressure.

Major-General Smith also notes that the presence of the navicular bone in the coffin joint increases the surface area of the coffin bone’s articulation surface area to almost as much as the short pastern bone’s articulating surface area. As the horse moves, weight comes down through the leg from the short pastern bone to the navicular bone which then has a slight downward yield, dissipating the concussion to the coffin bone. This redirects the force of impact to prevent a direct concussion to the coffin joint and, in turn, the coffin bone. The somewhat elastic collateral ligaments of the navicular bone (which are connected to the long pastern bone [P1]) are what give the navicular bone this function of “yielding articulation.” When the function of the ligaments breaks down, navicular syndrome can develop.

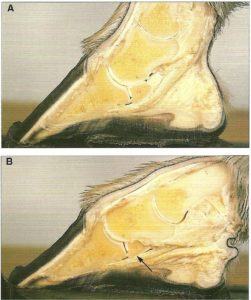

A)The navicular bone is under strain from the deep flexor tendon when the foot returns to its normal position and breaks over; B) The navicular bone is compressed by the short pastern bone (P2) when the foot is loaded. Reference: Pollitt CC: Color Atlas of the Horse’s Foot. 1995. Mosby-Wolfe, London. pg 44.

The fetlock joint also takes a lot of strain under movement. For this reason, the sesamoid bones aid in reducing concussion to the fetlock joint the same way that the navicular bone does for the coffin joint—with “yielding articulation.” Another name for the navicular bone is the “distal sesamoid.”

The deep flexor tendon is the main support of the navicular bone as it passes over the navicular bone and attaches to the semi-lunar crest of the coffin bone. The navicular bone is compressed by the deep flexor tendon each time the horse moves. The navicular bone is also said to be a fulcrum to keep the pull of the deep flexor tendon constant at its insertion on the coffin bone. This prevents the tendon from being pinched in the coffin joint during movement. The same can be said of the sesamoid bones at the fetlock joint.

The greatest amount of friction between the navicular bone and the deep flexor tendon takes place not when the navicuar bone yields under the weight of the animal when the foot comes in contact with the ground but when the bone returns to its normal position. This was confirmed by Smith when he discovered that the fibers of eroded deep flexor tendons on navicular horses were stripped upward instead of downward. This makes sense as the greatest amount of force against the bone would occur when the deep flexor tendon is flexing.

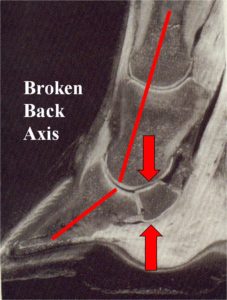

Broken back axis creates even more pressure on the navicular bone. The navicular bone is crushed from above by horse’s weight and crushed from below by deep flexor t. pressure. The results can be painful and lead to navicular bone remodeling as well as low ringbone on the pinched extensor process of the coffin bone. Reference: Roy Pool, DVM, PhD Equus 176, June, 1992.

The navicular bone has a miraculous function in aiding the horse’s movement and protecting the coffin joint. However, because of its position under the deep flexor tendon, the navicular bone is always under pressure even when the horse is standing still. The only relief the deep flexor tendon gets is when the horse lies down. This is not true of the hind feet because a horse can rest each hind foot by shifting its weight; using the stay apparatus locking mechanism of the stifle joint. When the horse bends the hock, the pressure on the deep flexor tendon and in turn the navicular bone is relieved. For this reason, navicular syndrome is rare (but possible) in hind feet. Horses bear 60% of their body weight with the front limbs. This is another reason why navicular syndrome is so prevalent in front limbs.

If the horse has an underrun heel conformation or a “broken-back axis” the navicular bone will be under even more constant strain from the deep flexor tendon. The trend to trim all horses’ heels back to the widest part of the frog is unwise because it can create a broken-back axis and cause excruciating results for the horse that is already afflicted with navicular syndrome. It is important to have a competent farrier regularly balance the individual horse’s feet through proper trimming and sometimes shoeing.

The principle of treatment for navicular syndrome is to relieve the pressure on the deep flexor tendon and navicular bone (and connecting ligaments) by raising the angle if necessary and to support the back half of the foot with a bar shoe. A bar shoe prevents the heels of the horse’s foot from sinking in soft dirt. This prevents further strain on the tendon and navicular bone. It is comparable to a person wearing snow shoes to prevent sinking in the deep snow. The wider surface area of the shoe helps to “float” the foot on the soft ground. Horses that develop navicular syndrome can often be maintained with this sort of treatment. It is not a death sentence for the horse.

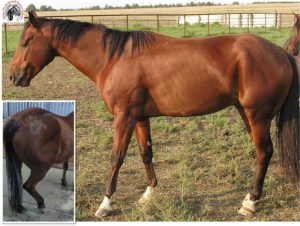

The classic stance of a horse with navicular syndrome is to point the foot that hurts the most. This puts the weight more on the toe and off of the heel. Front feet are much more susceptible to navicular syndrome because of constant weight bearing. Inlay: Hind feet are able to get relief on the deep flexor tendons when the horse bends the hock. For this reason, navicular syndrome is less likely in hind feet.

Related Posts

-

During the winter months, a lot of horse owners opt to have ...Dec 06, 2018 / 0 comments

-

There is a tendency in our modern society to look for short ...Dec 01, 2009 / 0 comments

-

Hospital treatment plates are used when the bottom of...Jan 11, 2018 / 0 comments

Blog Categories

- Anatomy

- Best Business Practices

- Conformation

- Current Events

- Customer Service

- Draft Horse Shoeing

- Equine Soundness

- Essential Anatomy Kit

- Farrier Careers

- Farrier training

- Foal soundness

- Horse Care

- Horse Foot Care

- Horse Owner Tips

- Horsemanship

- Horseshoeing

- Horseshoeing History

- Iron and Forge Work

- Student Spotlight

- Uncategorized

- Veterinary Care

Blog Archives

Contact Us

Butler Professional Horseshoeing School

495 Table Road

Crawford, NE 69339

(800) 728-3826

jacob@dougbutler.com

Subscribe to Our Blog

Get Our Free e-Book!

If you think you want to become a farrier (or know someone who does), this book can help you make that decision. Horse owners will learn the importance of choosing a qualified farrier and how to select the “right” one.

[ Get the e-Book Now! ]

- Follow: