Cushing’s Disease

Abnormal, uneven fat deposits particularly over the eye and crest of the neck are characteristic of a horse (or in this case, a mule) with Cushing’s disease. Photo credit: BPFS

Equine Cushing’s disease has become more of a concern to horse owners in recent years as the condition has become more prevalent. Equine Cushing’s disease is not a new problem. It has been around for a long time but it is receiving more attention because people seem to be keeping horses longer. Equine Cushing’s disease is typically an affliction of older horses (20 and older), but some cases have been reported in younger horses. The syndrome, also known as pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID), is a hormonal disorder in the pituitary gland of the brain. A tumor develops on the pituitary gland and causes an overproduction of cortisol in the system.

In a normal, healthy horse the pituitary gland produces Adreno Cortico Tropic Hormone (ACTH) which is responsible for regulating cortisol in the horse’s system. Cortisol is produced by the adrenal glands (next to the kidneys) as a natural response to stress. Its purpose is to help the body use glucose (sugar) and fat for energy (metabolism). In a horse with Cushing’s disease, a tumor on the pituitary gland causes too much ACTH to be produced. This alerts the body to continue to produce cortisol. When too much cortisol is produced, it inhibits insulin from absorbing glucose in tissues and regulating sugar levels. This overproduction of cortisol is what causes Cushing’s disease.

Recognizable symptoms of Cushing’s disease include: excessive hair growth, uneven fat deposits over the neck and belly, muscle weakness in abdomen and back (sway back), excessive sweating, frequent drinking and urination. The outward signs of Cushing’s should alert the owner to more serious inward symptoms. Horses with Cushing’s disease are at much more risk for Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) leading to laminitis and founder. Laminitis and founder are made worse by the overabundance of cortisol in the horse’s system because it prevents insulin from absorbing glucose in tissues. Insulin resistance happens when insulin can no longer allow glucose in the cells. Dr. Frank Gravlee of Life Data Labs, Inc. says that these horses are predisposed to laminitis because the laminar tissue (in the horse’s feet) is starved for glucose. Dr. Pollitt in Australia found that laminar tissue, without adequate glucose, is much weaker and therefore easier to separate from hoof and bone.

There is no cure for Cushing’s disease but there are medical treatments available to alleviate the symptoms. Prascend®, a drug with the active ingredient pergolide, is given with the goal to decrease the overproduction of hormones. These drugs can be very expensive (as much as $60 per month) and must be administered daily. The horse should be seen by a veterinarian regularly (at least twice a year). It is important to remember that the drug is only temporarily prolonging the horse’s life. Eventually, the condition gets worse and causes the fatality of the horse.

Feeding horses with Cushing’s disease can be frustrating. Because a horse with Cushing’s disease looks underweight, the natural inclination is to feed the horse more, but this can cause more problems. The horse needs more protein; not more carbohydrates or sugars. Feeding too much carbohydrates (grain), fat (senior feeds), or sugars (fresh pasture grass), will exacerbate laminitis and cause the horse to go lame. The horse is not likely to return to a healthy-looking body type. Most horses with Cushing’s have a pot-belly and sway back, but they can be maintained to have a relatively healthy life as long as the diet is closely monitored.

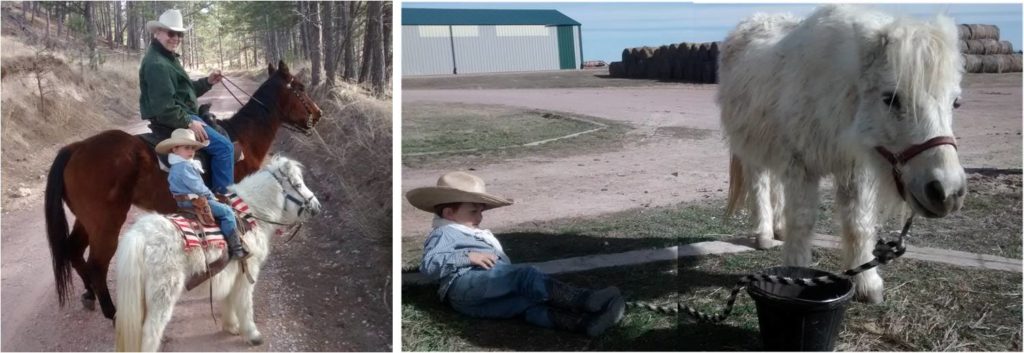

A good-natured pony was donated to Butler Professional Farrier School a few years ago. He was excellent with children. My young kids learned to ride on him. The pony developed Cushing’s disease in his later years. He lost weight so we had to feed him more protein, but not more carbohydrates or fat. If he had the slightest stressful episode, his laminitis was triggered and he would become lame. Heart-bar shoes offered a lot of relief as he was able to put weight on his frogs instead of his hoof walls. He had a good quality life and continued to be ridden by the kids for many years. In the end, the condition caught up with him, as it does with all horses that contract this serious disease.

My son (age 4 in these pictures) riding the pony with his grandpa, Dr. Doug Butler. This pony with Cushing’s disease had a longer than expected life because of proper care and nutrition. Because he also developed laminitis, the pony was more comfortable in heart-bar shoes. Note the characteristic excessive hair growth. Horses with Cushing’s disease often do not shed their winter coat, even in the summer time. Some owners opt to shear the animal to make them more comfortable in the summer heat.

Farriers should learn all they can about the disease so they can recognize the symptoms and offer recommendations. They should be able to help the horse to be more comfortable by trimming the horse in balance and if necessary, apply frog support. They should also be able to refer a good veterinarian that can help the horse medically. Horse owners should learn all they can about the nutrition requirements so they can care for these horses appropriately. At Butler Professional Farrier School, we have worked on several horses with Cushing’s disease. These horses were able to live long, quality lives because their owners took good care of them.

Related Posts

-

Last week (Can it be Fixed?), we talked about crooked-legged...Dec 21, 2017 / 0 comments

-

Horseshoes can (and should) be modified to be more beneficia...Mar 07, 2019 / 0 comments

-

Answer: A hoof that is proportional to the horse’s bod...Dec 07, 2009 / 0 comments

Blog Categories

- Anatomy

- Best Business Practices

- Conformation

- Current Events

- Customer Service

- Draft Horse Shoeing

- Equine Soundness

- Essential Anatomy Kit

- Farrier Careers

- Farrier training

- Foal soundness

- Horse Care

- Horse Foot Care

- Horse Owner Tips

- Horsemanship

- Horseshoeing

- Horseshoeing History

- Iron and Forge Work

- Student Spotlight

- Uncategorized

- Veterinary Care

Blog Archives

Contact Us

Butler Professional Horseshoeing School

495 Table Road

Crawford, NE 69339

(800) 728-3826

jacob@dougbutler.com

Subscribe to Our Blog

Get Our Free e-Book!

If you think you want to become a farrier (or know someone who does), this book can help you make that decision. Horse owners will learn the importance of choosing a qualified farrier and how to select the “right” one.

[ Get the e-Book Now! ]

- Follow: