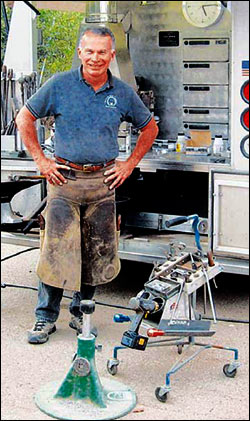

At Work With: Chris Minick, Farrier

By JoAnna Rodriguez

SPEAKING “equine” is an imperative part of Chris Minick’s work shoeing and caring for horses’ hoofs. That’s because knowing if a horse is frightened, impatient or just uneasy can make all the difference when it comes to his safety. “Just about any horse can injure me immediately,” the farrier said. “You have to constantly gauge the signals of the horse.” We talked with him about keeping horses’ feet healthy and why a good farrier is always in demand.

How did you get involved in the field of shoeing horses?

I was 20 and living on a 22,500-acre ranch. We had 50 head of horses that had to be shod and only old men to do the work. My father-in-law sent me to farrier school in Golden, Colo. When I graduated, I started making more in one hour than I did in an entire day on the ranch. Horse owners from up to 100 miles away started calling me to shoe their horses. What kinds of horses do you shoe and for what activities? I work on all kinds of horses, for everything from shows to the U.S. Park Service. I even trim some miniature donkeys.

What’s the process you go through when you’re working on the horses?

There’s so much involved that there are books written on it, but the basics are I take off the old shoes, trim the hoof, sole and frog, level off the entire foot and then decide what shoes will fit their feet. After I’ve shaped the shoes — either with the propane forge or cold if little adjustment is required — and I’m certain the shoes are a good fit, I nail them on. The nails must be driven in just right or you can cause the horse a lot of pain or make them “nail bound,” where they will feel the pressure of the nail from displaced tissue. I then cut off the excess horseshoe nails and clinch them down so that the shoes don’t come off. The nails are buffed clean and a sealant is applied to the finished hooves. All of this happens in about an hour’s time for a complete shoeing. It’s very physical work. There are additional steps when I’m working with a new horse for the first time.

What’s involved in working with new horses?

Much of my time is spent evaluating how comfortable the horse is with me. I watch them walk, trot and sometimes cantor to see if they favor a foot, if the feet land flat on the ground, how high they pick up their feet and how their old shoes are worn. I also evaluate the quality of workmanship of the previous farrier and look at whether or not the feet are matched. The evaluation process alone is very involved. I also consider how the owner will use the horse, the terrain it will be on and the long-term needs for keeping the horse sound and active. All of these things impact my work.

What are some of the rewards of your work?

I greatly enjoy the horses and interacting with their owners. Horses are always honest and genuine. I can tell immediately if they trust me, if they are beginning to get impatient, or if they want their foot back (before they jerk it back). When I leave a job, I feel good about myself and the work that I’m doing. I make a difference and a good income.

What are some of the challenges?

One of the biggest challenges I face is inheriting horses whose feet have been damaged by poor farrier work or neglectful owners. Owners often have unrealistic expectations of repairing the damage, which is why I have case studies of work that I’ve done. I can show clients the progress [of the foot] from when I took over to what we achieved in the end. Another challenge is safety. Sometimes clients don’t want to help you with a horse that’s unruly, but if I’m going to work on their horse they need to be concerned about my safety. Just about any horse can injure me immediately and it’s the ones who explode without warning that you need to be the most concerned about. They don’t deliberately try to hurt me, but they hurt me trying to get away. Just last week I was stepped on by a 2,400-pound Belgian draft horse, which is a little more than double the size of your average riding horse. Two-thirds of her weight is in the front, so one foot is 800 pounds. I was lucky that she just got the side of my foot. I’ve learned to move pretty quickly and get out of the way.

What skills should a farrier have?

You must have genuine concern for horse’s welfare and have a lot of patience. You need to be able to analyze a horse’s gait and have a solid understanding of anatomy, blacksmithing, welding, metallurgy, pathology and nutrition, among other things. You also need good horsemanship skills because you can’t work on a horse that’s moving around. You need to understand why the behavior that’s preventing you from doing your work is happening. Is it out of fear or because the horse is uncomfortable? The average horse is seven times larger than me, and you can just feel it when they are tense. You have to constantly gauge the signals of the horse.

What is your training and what schooling would you recommend?

I initially attended a three-month training program at a school in Golden, Colorado. Since then, I’ve attended farrier clinics every year to learn about new techniques and technologies that can be applied to the craft. When it comes to choosing a school, I’d recommend the Butler Professional Farrier School in Nebraska. You are held to a very high standard and will be prepared for every aspect of the business.

Is certification necessary?

No. Basically anyone could go buy rudimentary tools and call themselves a farrier. Unfortunately, people generally don’t know good work from bad until it’s too late, and the horse is hurt. There are probably 80 or 90 farriers in the North Bay, but only about 10 of us are certified by the American Farrier’s Association. Getting certified is tough and when I took my hands-on horseshoeing test only two out of 17 people passed. There is also a written exam and a shoe-making test to get your certification.

What are some of the specializations in your field?

You can specialize in shoeing horses for races, endurance, dressage, hunterjumper, Western and eventing. You can also be an expert at things like dropped soles, club feet, laminitis, thrush eradication and just about any kind of custom work imaginable.

How much could a farrier hope to make?

The American Farrier’s Journal estimated in 1998 that the average full-time farrier grossed $55,723. Farriers on the East and West coasts gross about $10,000 per year more than the rest of the country, but it’s definitely possible to make more than that. I have a colleague with a multi-farrier practice who enjoys a $200,000 plus income. In fact, farriers just out of school generally make more than veterinarians just out of school.

What’s your advice to prospective farriers?

Read as much as you can about the business. I constantly pick up new books and subscribe to the American Farrier’s Journal and the trade magazine Professional Farrier. A good book to read is “Six-Figure Shoeing,” by Dr. Doug Butler, who is the world’s most renowned and recognized farrier educator. This book will truly help you determine whether you are suited to building a business as a professional farrier. It’s a very down-to-earth business and a good farrier is always in demand. Also, it offers a flexible work schedule, and you can be your own boss.

Essential Principles of Horseshoeing

Discover a new interactive way to learn the principles of horseshoeing and humane horse foot care! Essential Principles of Horseshoeing is the latest book now also available in audio format from Doug Butler Enterprises that uses detailed graphs, charts and QR codes that take readers to video demonstrations, just as though you were sitting in the classroom!

Contact Us

Butler Professional Horseshoeing School

495 Table Road

Crawford, NE 69339

(308)665-1510

jacob@dougbutler.com

Subscribe to Our Blog

Get Our Free e-Book!

If you think you want to become a farrier (or know someone who does), this book can help you make that decision. Horse owners will learn the importance of choosing a qualified farrier and how to select the “right” one.

[ Get the e-Book Now! ]

- Follow: